For more than a century, furniture has been the heartbeat of downtown High Point. But as manufacturing jobs moved overseas, and showrooms sat empty for most of the year, the city realized more was needed to restore its sense of pride.

***

IT’S A SWELTERING SATURDAY MORNING IN LATE SEPTEMBER, and the High Point Amtrak station overhang is the spot to catch some shade. About two dozen locals congregate on benches outside the railroad depot, sipping bottled water and liberally applying sunscreen. The noon sun peeks through patchy clouds, sending sweat dripping down folks’ faces. The heat is oppressive, but clear skies of any kind are welcome one week after Hurricane Florence crippled communities across North Carolina in record-breaking fashion. Rain or shine, no one wanted to miss lawyer Aaron Clinard’s tour. The 71-year-old is a mainstay in High Point happenings, a veteran voice on the roller-coaster ride to revitalize the city’s downtown. Clinard arrives dressed for success, sporting tan slacks, a navy blazer and brown moccasin loafers. He’s an entertainer at heart, the kind of thoughtful explorer who was born ready to be your guide. It’s not quite lunchtime yet, but Clinard readies everyone for life after the tour, with a copy of his exclusive “Concierge’s Restaurant List” of High Point’s best places. He picks up his bullhorn from a library staff member, beaming with pride. “Test! Test! Good,” he shouts.

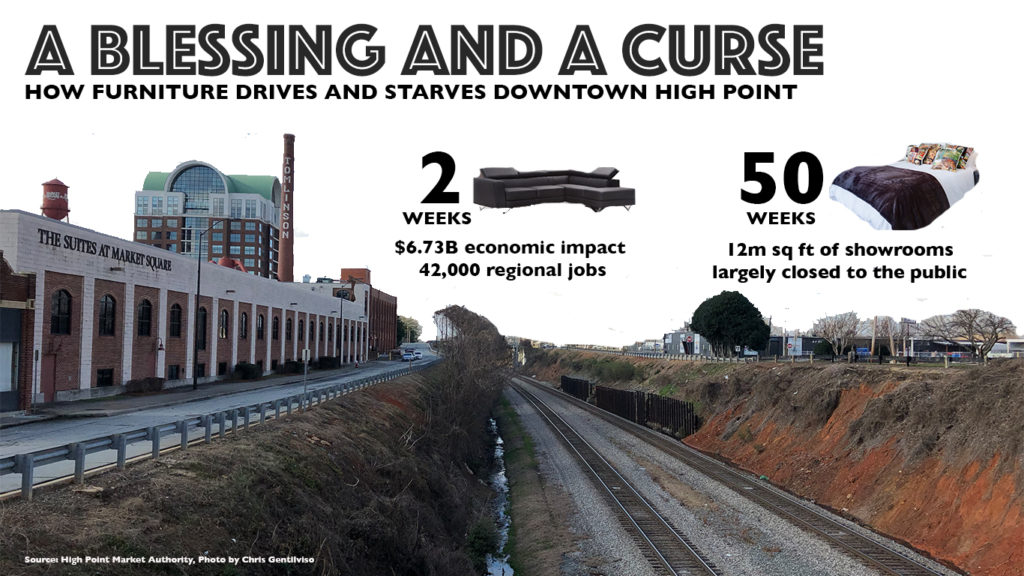

Clinard could make the case for High Point’s legacy in his sleep. This isn’t any old train station. It’s a key marker on the Fayetteville and Western Plank Road, the Civil War-era thoroughfare that lifted North Carolina commerce out muddy ditches and slave labor. It’s the “High Point” between Goldsboro and Charlotte, the inspiration for the city’s name. It’s the asset that paved the way for an international reputation in the furniture and hosiery industries, with dozens of factories up and running by the 1920s. It’s also a reminder of how the South afforded greater potential to some than others. “You see exactly what was done in 1907,” says Clinard, referencing a $6.8 million renovation project in 1984, which saved the original depot. “Except for one thing, and this is a good thing.” He raises his finger toward the sign above. “They had white and colored bathrooms. We don’t have that anymore. Thank goodness.”Something else is missing on a Saturday morning: foot traffic. “You stragglers gonna get left behind if you don’t come on!” Clinard wryly warns as he speeds ahead. “I don’t know how he’s wearing that jacket,” says another attendee. We walk past the site of the 1960s Woolworth’s sit-in that helped set the Civil Rights Movement in motion. Some of High Point’s earliest settlers were Quakers, and while more tolerant than other cities, it was still the South. A native of nearby Thomasville, Clinard’s drawl competes with the hum of car engines whizzing up and down Main Street. As we scamper across the street, drivers gawk as if we’re a set of lost ducklings, a group too large to be here today. “Market” – the bi-annual furniture gathering that pumps in nearly $7 billion each year – isn’t in session. As we stand in front of the Southern Exposition Furniture Building – a towering 10-story structure which cost around $1 million to build in 1921, we see the entrepreneurial spirit that put High Point on the map. “I said earlier to Chris, it’s almost like the blessing and the curse for our city,” Clinard tells the group. There’s money everywhere, but in this one industry town, few people are lucky enough to reap the benefits of furniture’s inside circle.

When Clinard entered adulthood in the late 1960s, he couldn’t wait to get to High Point. The city’s population crested above 60,000 people. The hosiery industry had a household name in Adams-Millis and its $20 million in revenue. The furniture showrooms were expanding like mad, with 375,000 square feet of additions. But toward the end of the decade, downtown activity moved from a manufacturing center to a service climate. Newly-annexed suburban neighborhoods had the same city services and lured families away from Main Street living. By the 1990s, three million more square feet of showrooms came to town, but jobs lagged behind. The furniture industry’s decline was accelerated by threats from Asia. An October 2018 Economic Policy Institute study estimated from 2001 to 2017, three percent of all jobs in North Carolina were lost to a trade deficit with China. The 2008 Great Recession was a devastating tipping point for furniture, as revenue fell by 21 percent. High Point’s overall tax base was slashed by 11 percent. Across North Carolina, 60 percent of furniture positions have evaporated since 1990. And now, almost 350 days a year, a common word in downtown High Point is “CLOSED.” “When the furniture market is here, it’s like being in New York,” Clinard argues, mentioning my hometown, the vibe that made me think High Point’s potential was dormant, not defeated. “The curse is that when they leave, they’re gone and our city, our downtown, is dead.”

***

AT “MARKET” LAST SPRING, I learned exactly what Clinard was talking about. Rolling luggage bags overtake High Point’s usually empty sidewalks, with airport tags from as far away as Hong Kong. Storefronts shift from locked to revolving, offering coffee and grab-n-go breakfasts. More than 2,000 exhibitors from 112 countries crisscross 12 million square feet of displays, cutting the best deals for their businesses. But were there any brands with a real stake in High Point, a set of roots beyond two five-day stays in April and October? Or is “market” just the furniture industry’s version of Airbnb?

Very few big-name brands like Broyhill or Thomasville still assemble their pieces in North Carolina. According to the state’s Furniture Export Office, only 24 businesses meet the “Made in NC” standard, which factors in headquarter locations, as well as labor and raw goods sourced in state. At 310 South Elm Street, just a few blocks away from the Southern Furniture Expo Building, Braxton Culler is one of them. Its low-lying storefront looks more like a 1950s car dealership, with a silver, block-lettered logo straight out of a vintage movie. The genteel feel is a testament to the company’s 45 years in the community.

Inside, the welcome desk fields a homegrown look, an inviting set of yellows, reds, pinks and greens, fit for a drive to your timeshare along the Carolina coast. Toward the left is a short spiral staircase, where Chief Operating Officer Braxton Culler IV is waiting. He’s around six feet tall, with a round face, broad shoulders and sturdy build. His casual tan khakis, chic black blazer and slip-on black loafers rival Mr. Clinard’s closet. It’s no wonder they’ve both served on the board of the String & Splinter Club – the pre-eminent space for High Point’s business elites to wine, dine and network. There’s a male-dominated Mad Men vibe, with wealth and social mores found on Don Draper’s Madison Avenue.

Nicknamed “Brack,” Culler has a tiger-like stride, a baritone voice, a firm handshake and a wall of loyalty for his hometown. We sit perpendicular on a long, white sectional sofa, made at a factory just down the road in Randolph County. At one time, this showroom was full of young patrons looking to fill their homes. “People who are 25, 35, 40 years old — that is the consumer to whom we are directing our marketing,” Braxton Culler told the New York Times at the 1985 market.

Now, I’m sitting with his great grandson, pondering what High Point looks like for the next group of 25-, 35- and 40-year-olds. Brack’s three kids were sixth-generation, ages 10, 14, and 16, and they may prefer rental apartments up the street. The sofa’s cushions were soft as a feather and hard to top. This was Brack’s 48th market, but the goal for the company isn’t fancy: sell furniture, add floor placements and meet new dealers.

As Brack stares out the window toward the Amtrak tracks, he sees the String & Splinter, where his great grandfather worked as a kid. Just like Mr. Clinard, Brack wishes more places like that were still in town. Furniture grew the economy, but toppled mainstays like Noble’s Restaurant and the Elwood Hotel. Smaller cities seeking a makeover often start with downtown. But showrooms on every street corner complicate High Point’s remodeling job. “There were tons of gorgeous buildings that were torn down because of the furniture industry,” Brack laughs, wiping a smudge on his shoe.

Braxton Culler is one of the few businesses to tough it out. Their most valuable piece of furniture isn’t a bed or a couch, but a third eye on customers. “Do you need me to walk with you?” Brack asks a group as they sifted through living room sets. “Do you want me to answer questions?” “We’re okay,” a woman answers softly. But her tone suggests help may be welcomed later. “We’ll take pictures so we can see.”

“All right, I’ll be right here,” he says calmly.

The baseball stadium has yet to break ground, but Brack feels the wheels turning. He knows why young folks are hesitant to stay in High Point. After graduating from college, he moved to Greensboro because there was nothing to do at home. “This stadium moving forward is going to put us back on the map and make us relevant again to millennials,” he vows.

They likely won’t be working in furniture, though. Brack admits he sounds old, but younger people are entering the industry more slowly, especially sales reps. “A lot of these people, they think sending an email is calling an account, or servicing an account,” Brack laments, with his own iPhone unwillingly glued to his side. “You’ve got to get out there and go in the car, drive, meet, face to face, interact with people.” Then comes a long pause. Brack couldn’t count how many mom and pop stores closed in recent years. Fewer local spots meant fewer dependable regulars. Big chains were an issue and the internet’s eCommerce binge added more complexity. “That’s my biggest question mark,” he wonders. “What is the interaction with people going to be like in 10 years?”

So, young people probably weren’t going to put springs in the sofa we were sitting on. But furniture wasn’t going anyplace. New showrooms were still coming to town. “The Bank on Wrenn: High Point’s new must-see luxury showroom destination. Opening fall 2018.” “Art Addiction: the largest art showroom in High Point. Opening spring 2019.” Brack remembers when “Vegas scared us.” Rumors swirled in the mid-1990s that High Point would lose Market to Sin City. “There’s too much infrastructure for it,” Brack says, arguing mirrors and rugs would always have some place in High Point. But would younger generations fit in that future?

“I mean, this would be the stadium,” Brack supposes. “High Point University has been monumental in keeping us on the map. Putting us on the map, really.”

High Point University president Nido Qubein knows this too. When he was a student at the school in the late 1960s and early 1970s, it was a tiny piece of the city’s fabric. But over the last decade-and-a-half, HPU increased its student body (1,450 to 5,200 undergraduates), full-time faculty members (108 to 316) and campus size (91 to 460 acres). As the footprint grows, so does its presence. Pamphlets at the String & Splinter showcase special rates for students, faculty, staff and alums. Back at the Braxton Culler showroom, the Pretenders’ 1979 hit, “Brass in Pocket,” begins playing over the speakers. Even though millennials were first born in 1981, there’s hope that downtown High Point’s catalyst project is “gonna make you, make you, make you no-ticeee.” If HPU is the key, if business people like Brack had it their way, what’s the ideal Main Street?

“Not what it is today, but what it could’ve been?” Brack asks.

“Yeah, the aspirational Main Street,” I reply.

“Retail storefronts, boutique hotels, restaurants,” he says.

“Chapel Hill?”

“Right.”

***

QUBEIN IS A MAN WHO TURNS ASPIRATIONS INTO ACTION. “It’s almost like he finds a way to get his hand into your pocket,” says one local of his fundraising prowess. “He’s bought everything from Thomasville on up,” says another. And yet, High Point’s growing pains are still formidable. “Winston-Salem has certainly done it,” Qubein said last year of the need for reform. “Durham has certainly done it. So, this is not exactly a unique idea.”

But High Point is unique, a stew of old and new blood with different approaches for moving forward. At the High Point Historical Society’s first meeting of 2019, baseball is off the agenda. The group mingles over mini chicken biscuits, petite cookies and K-cups of French roast coffee. They’re hesitant to be firmly for or against the Rockers, but they know change is brewing. “Everything really had gotten just on hold,” says native Anne Andrews, a member of numerous historical commissions, while loosening the collar of her thick, black turtleneck. “There wasn’t anything happening.”

Another High Point native, main presenter and local author Benjamin Briggs isn’t the stadium’s biggest fan, but he’s also not a vocal detractor. A mild-mannered, clean-shaven encyclopedia of area history, his hesitation comes from lessons learned in other places. Take Greensboro, where the 2005 arrival of a minor league baseball stadium transformed the city in unforeseen ways. Nearby apartments now rent for $1,500 per month. As a steward of sacred spaces, Briggs wants revival without losing buildings forever. He’s hoping a cottage within Oakwood Cemetery, a little brick oasis High Point planned to take down, can morph into a genealogy center for the relatives of the 5,000-plus people buried there. “Maybe we’ll get some conventions out of that, with family reunions that put heads in beds and fill up our hotels and our restaurants,” Briggs says, a subtle push away from grade-A gentrification.

When Qubein received his bachelor’s degree from High Point College in 1970, no one knew he would be the “bus driver” of the city’s 21st century entrepreneurship. But he’s the president of HPU, the chairman of a 220-store bakery chain, a board member of BB&T (the stadium’s primary sponsor) and the steward for a High Point’s new, diverse generation.

Jim Armstrong, an area historian, is ready to let go. His strong helmet of gray hair survived years of local debates on the Chamber of Commerce and other boards. His gold 1859 High Point Museum pin still shines on the lapel of his tweed jacket. But it’s time for younger people to take the spotlight and lead. “Look at what the hospital has been able to do!” Armstrong says forcefully, pumping his fist. “Right there with the ball stadium. They can look out their window and see a ball game!” He knows health care and HPU, not hosiery and furniture, are the city’s new top employers. At the end of the day, “infrastructure and young people are the two things revitalizing this core city.”

Andrews looks up pensively and can’t help but agree. “I think you’re right.”