High Point is in transition. While furniture is still a force, a hospital, a college campus and a new stadium are anchoring the city’s hope for year-round change. But some millennials are skeptical downtown will be their go-to place to hang out.

***

WHEN DR. NIDO QUBEIN GRADUATED FROM HIGH POINT COLLEGE IN 1970, his yearbook was stocked with prototypical campus memories. Flip through “The Zenith” and there’s a “spring fever” section, with students venturing to City Lake for a picnic, or McDonald’s for a burger. Back then, the fast food giant’s claim to fame was “over five billion sold.” On “entertainment” and “happenings” pages, the student union hosted a psychedelic light show. Admission: 50 cents. The basketball team had a long season, but still netted a full-page spot, with a brief cameo by current Head Coach Tubby Smith. Buried toward the back was a mention of America’s pastime – a half-empty set of bleachers, with a half-hearted caption: “warm weather and baseball attracts students.”

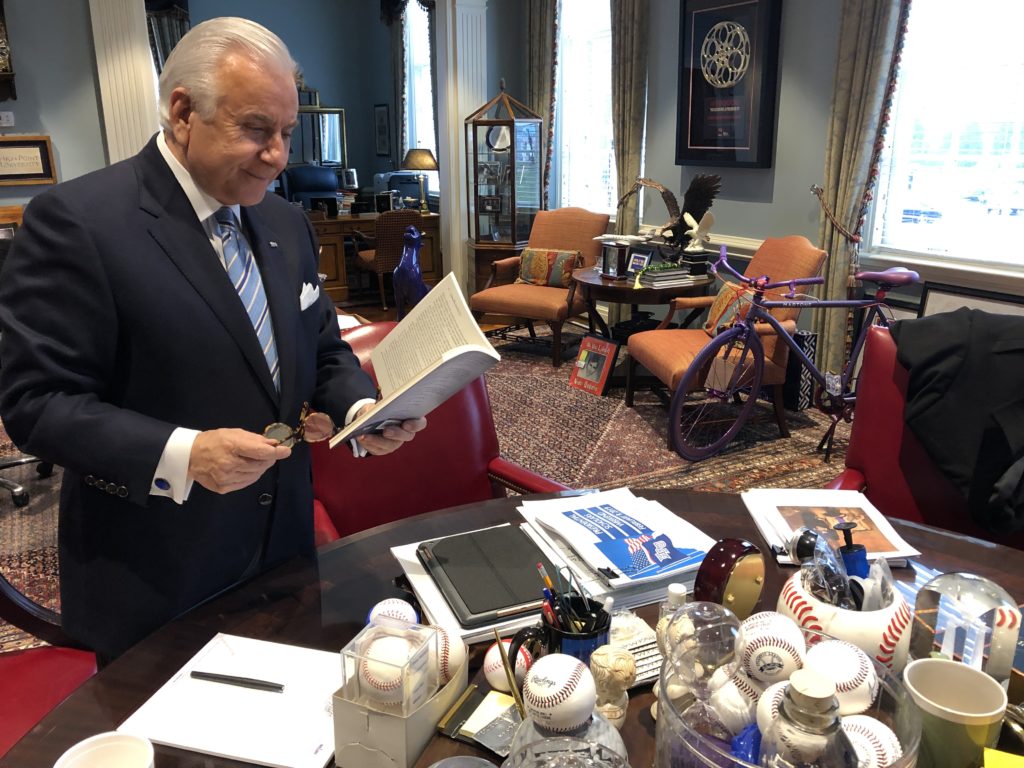

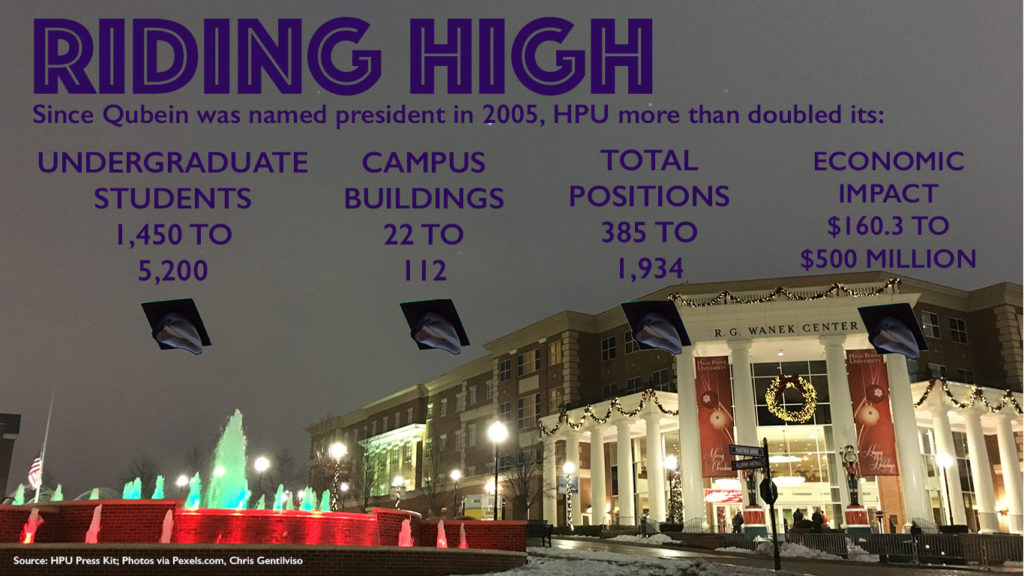

Of all campus buildings, Roberts Hall is still the crown jewel. Anchoring the 1970 Zenith “scenery” page, the college’s oldest structure stood “tall and dignified.” Almost 50 years later, so does Qubein inside his presidential suite. The elegant clock tower above him keeps tabs as High Point University grows like crazy. Since becoming leader of his alma mater in 2005, Qubein stewarded the campus’ growth in size (91 to 460 acres) and student body (1,450 to 5,200 undergraduates). He runs a tight schedule, but looks relaxed, donning a navy pinstripe suit and a Carolina blue tie. His royal blue, gold-plated cufflinks stick out like diamonds, strong enough to keep his sleeves and downtown revitalization plans together. His office is the size of a studio apartment, with room to park a fashionable Martone bicycle, painted in signature purple and white school colors. His desk is bookended by American flags, a freeze frame resembling the White House Oval Office. It’s just after 4 p.m. on a dreary, drizzly Wednesday, but Qubein’s energy rivals the morning sun as he wraps up an email. “It’s a beautiful campus you have here,” I say, as soft music fills the room. “Thank you, sir,” he replies confidently, knowing his moves made the amenities possible.

We shift toward a small conference table, with red leather chairs you could call home for hours. The surface is littered with “Atlantic League” baseballs, and in 100 days, the High Point Rockers will throw out one of these at their inaugural home game. Qubein didn’t come up with the stadium plan, but he’s carrying it across the finish line. For decades, High Point has tried to inject life into its downtown. In 1961, as the furniture and hosiery industries started to peak, the “downtown development committee” first sketched out a “plan for action.” “A prosperous CBD is everyone’s concern,” read page three. In 2013, “Ignite High Point” entertained discussions with world-renowned Cuban architect Andrés Duany. But as urban sociologist and DePaul University Professor John Joe Schlichtman argued in a Feb. 2019 Greensboro News & Record op-ed, Duany and other consultants “were never able to grasp the depth of what was occurring in High Point during their short visits.” Duany’s plans ruffled feathers, especially “pink code” zones where rules would be loosened to help start new businesses. Qubein turned out to be a superior force, surpassing a name whose firm designed a building in the opening credits of Miami Vice. In 2017, “Forward High Point,” the latest iteration of downtown re-development, asked Qubein to deliver a keynote address at the High Point Country Club. They had the idea for a team, but he says they didn’t have the money, or the drive. “This is about community pride,” Qubein tells me, never teetering off message. “This is not about a ball park. This is about the transformation of downtown.”

(Photo by Chris Gentilviso)

Ideas began to mushroom. What about a children’s museum? Or an events center? Qubein’s optimism quickly met the reality of costs. “I said, ‘I volunteer to raise the money,’” he remembers. “So that, of course, got big headlines in newspapers.” Raising millions was not a new hurdle for him – one of many, starting with his journey to America. Born in Lebanon in 1948, Qubein’s father died when he was six years old. At age 17, he flew from Jordan to the U.S. with $50 in his pocket. Qubein knew little English and, to pay his way through college, made money delivering motivational speeches at churches and civic events. He traversed the back roads of North Carolina, making connections in the faith community. Those ties helped him shift from an associate’s degree at Mount Olive College, to a home address. In the 1969 Zenith, “Nidal Raji Qubein” is listed at “211 Louise Avenue, High Point, N.C.” – native status, footsteps from Main Street. By 1970, he went by “Nido” in the yearbook. He met the right people, led by the inimitable Bill Horney, a local business owner and longtime economic development force, who died in 2018 at age 101. “People liked him,” said Horney in an Oct. 2003 News & Record profile of Qubein. “He was so enthusiastic.”

Qubein’s enthusiasm is now the glue of High Point’s future. Many moments are stashed in the president’s office – honorary degrees, awards and photos with celebrities from Condoleezza Rice to Josh Groban. But what’s most important? Qubein gets up and walks toward a map of campus, spreads his hands wide and says “This!” He knows the Recession was particularly painful for North Carolina’s Triad region. From 1990 to 2010, High Point’s population grew from 69,428 to 104,371 people. But the portion of workers in the labor force fell from 68.8 percent to 66.5 percent. Qubein’s doing his part by churning out more college-educated employees. He invested more than $1 billion in new classroom buildings and programs at HPU, such as communications, pharmacy and engineering. The school is a fixture in U.S. News & World Report’s heralded rankings: best regional college in the South (2013-19) and most innovative college in the South (2016-19). “Ultimately, I believe in two simple English words,” he says. “Results rule.”

But reviving downtown High Point is Qubein’s biggest challenge yet. His résumé includes board positions with BB&T bank, Great Harvest Bread Company, and La-Z-Boy furniture. His BB&T ties helped secure a 15-year, $7.5 million naming rights agreement for the stadium. But earlier in the day, a major local developer, Roy Carroll, pulled out of a deal to build a hotel. Qubein doesn’t flinch, and instead writes. “Judy, bring in a copy of the op-ed for Chris, please.” She hands me a printout. “Innovation is sometimes messy,” reads the first sentence of the Jan. 26 News & Record piece. The city pulled together $36 million in borrowed bonds to build the stadium. Qubein helped HPU raise $375 million over his tenure, so who’s counting? He steered $100 million in private money to support projects around the field. The baseball operation, the children’s museum and the new event center will all rest in 501c3s – nonprofits considered charities, which are exempt from taxes. Qubein vows no one around him will make a penny. But he still wakes up every morning with what he calls cautious optimism, until the vision is complete. “If it was easy, anybody could do it,” he says. “And we’re not looking for easy.”

When fans pile into the Rockers’ home opener on May 2, 2019, it will mark a new day in High Point – a multi-purpose facility well beyond what students in those half-empty 1970 park bleachers could have expected. Qubein counts his fingers, one by one – the uniforms, the team office desks and chairs, even the garbage cans. “All of that – all of which is money I raised.” The music overhead shifts from soft to jazzy, as if the speakers know he helped sell out luxury boxes for the Rockers’ inaugural season. At age 70, Qubein says he no longer wants to display awards. He seeks experiences, moments that come to life, at a baseball game perhaps. “Money doesn’t grow on trees, but people become the branches,” I say, a pitch for his next book of motivational quotes (he handed me a copy on the way out). “Yes!” he replies. “Exactly.”

***

INSIDE THE STRING & SPLINTER CLUB, Qubein’s bullish actions are driving the buzz. Fifty years ago, “Chamber Cheers” would have been dominated by an inner circle of white, male furniture and hosiery leaders. Tonight is different. The Chamber of Commerce is celebrating its 100th year, and while the sidewalks along High Avenue are desolate, the String & Splinter Club is bustling with vintage charm. Guests are met with a red carpet at the entrance, an accessory that would pass in Hollywood. Olde English lettering on the front awning gives off an exclusive vibe, and inside, the feel of importance persists. Members mingle in private rooms holding 10 to 80 guests, equipped with plush, crimson red armchairs, oriental rugs, southern menu favorites and a front-and-back wine list. Just on the other side of the Amtrak tracks, massive cranes are moving steel beams into place to set up the seats at BB&T Point stadium. The yellow foul poles are up and the baseball diamond is on its way.

Up on the second floor, Brittany Butterworth is tearing off drink tickets, directing guests to hang their coats and keeping the “Chamber Cheers” trains moving. She’s full of energy, as her event photography business serves as lead sponsor for the new happy hour series, which just turned two. In the background, “Miss Nicki” Skipper makes sure the tables are set. She’s approaching her fourth anniversary as general manager of the String & Splinter. Before moving into this picturesque space in 1983, no women were admitted. “We are, and it’s not a secret, please spread the word,” Miss Nicki tells the crowd of about 50 guests. “We are where the City of High Point leaders meet since 1957 … And please see Will. He’s dying to pour you a glass of wine, or pop you a beer.”

It’s the New Year, and while the smell of the hors-d’oeuvres is making stomachs growl, folks are committed to reach their resolutions inside the gym. Hilton Ferguson of Full Time Fitness is a chiseled black man, with long, tight dreadlocks and a wide smile. His neck is thick, his physique capable of training the best athletes out there. “All right, hello, hello, hel-loooooo!” he projects out into the crowd.“How are you folks doing? I see a lot of familiar faces here.” Full Time Fitness is a familiar name in High Point, but a decent drive from downtown. About seven miles north on Highway 68 is the Palladium, a sprawling strip mall, with a free-standing Belk department store, a 14-screen Regal movie theater, a Starbucks, a Chick-fil-A and more. Ferguson and his wife, Kit-Tena, are the exact type of business owners missing from the downtown fabric. The closest gym in the downtown area is inside Wake Forest Baptist Hospital. Unless you’re a hospital worker (the city’s top employer in 2018), it’s an unorthodox place to head for a post-work yoga class or boot camp. “The CDC recommends we do about 150 minutes of exercise per week,” Hilton says wryly, with a smile. “So, it’s Thursdayyyy.” The crowd bursts into laughter. “How many people have done 75 minutes of exercise thus far? Ok, that’s good. Anybody at 100 yet?” The groans drown out the chuckles.

But it’s a groan of optimism. Just five years ago, a new HPU professor wandered onto city-data.com, seeking advice on rentals in downtown High Point. “Something like an above-storefront loft or apartment,” the note read. “I’ve spent the last few weeks trying to search for options – I’ve even “Google mapped” myself up and down the streets, looking for “For Lease” signs in second-story windows — but to no avail.” A few replies down, one comment warns: “You will discover HPU is a very, very nice compound with its huge brick and rail fence that screams ‘keep out!’ Although HPU has exploded in growth in recent years the city surrounding the campus has little to offer. Good luck to you!”

Tonight, there are signs of what the city has to offer – an entrepreneurial Main Street, where an event photographer and a personal trainer anchor the first 2019 Chamber of Commerce conversation. There’s a younger generation sharing wedding photos online and forking over money for a gym membership. Next year, around 200 rental apartments were slated for construction. This is Qubein’s vision of fellowship – a place where friends gather and make their own kind of connections, just like he did.

***

IT’S JUST BEFORE 8 P.M. AND QUEEN’S “FAT BOTTOMED GIRLS” CAN BE HEARD HALFWAY DOWN SPRING GARDEN STREET. The parking lot is already full at Jake’s Billiards, so I’m lucky enough to grab a spot near the curb. After the crowd wound down at Chamber Cheers last week, I took Miss Nicki’s advice and got to talking with Will. He warned places close early in High Point and wasn’t kidding. Brown Truck Brewery shuts down on Fridays at 11 p.m. Blue Rock Pizza was also open only until 11 p.m. What about Blue Bourbon Jacks or HPU hotspot After Hours Tavern, which actually stayed open until last call? About an hour earlier, Will texted me, “We’re thinking downtown Greensboro for overall ease tonight.” Exactly 59 years ago, four African-American students from North Carolina A&T made history, staging a sit-in for civil rights at the Woolworth’s lunch counter. Today, Elm Street was the strip of bars and restaurants where all of us, no matter how we looked, kept the fun going until 2 a.m. I grabbed a room at the Hampton Inn down by the coliseum for the night. Will’s friend, Curtis, took an Uber from nearby Randleman, and Will’s dad gave them a lift from his house in Jamestown. His address is close enough to the border that “High Point” works in Google Maps, too. Three cars and three rides later, we were all here.

As I walked up the steps at Jake’s, the corn hole courts were packed with people, sipping drinks and throwing their best tosses. More than a dozen TVs rotated between Friday night basketball games that might as well have been on mute. Queen’s greatest hits were gradually replaced by grungier punk rock. We were footsteps from the UNC-Greensboro campus, where Qubein received his master’s degree in business in the early 1970s. Over the last 15 years, much has changed. Greensboro was the first city in North Carolina’s Piedmont Triad to use minor league baseball as an economic catalyst. About two miles down the road, the Greenway at Stadium Park apartments line the outfield fence of First National Bank Field. Starting at $1,425 per month, it’s where “luxury and elegance meet sophistication,” the rental website reads. Across the street, Millennials sip beers on the patio of Joymongers Brewing Company, a small-batch shop owned by Greensboro natives. Winston-Salem repeated the recipe in 2010 with its own stadium, BB&T Ballpark. Now there are chic lofts for rent, and local café hideaways like Krankies, a converted meatpacking space. Why not High Point too?

“Chris!” yells Will at a low-lying picnic table off to the left. He just got off a shift at the String & Splinter, trading in the all-black bartender’s uniform for light tan khakis, a red polo and chukka boots. Like Qubein, his hair is neatly parted, and at age 25, he is the ideal alum for HPU – an area native, a bachelor’s and M.B.A. holder, and a person who wants to live and work in the region. But when Will hears about the new apartments being built near BB&T Point stadium, he doubts one of those addresses is a fit for him. His mom walked out during his freshman year in college. He didn’t want to get into numbers, but “my student loan, my car loan, everything associated with that, living expenses to go out on the weekend, go out on dates,” he says. “I would have zero money left at the end of the month if I paid all of that plus $700, $800 in rent. It makes so much more sense to live in my dad’s four-bedroom house for free and just clean the place once a week for him.”

(Photo by Chris Gentilviso)

Curtis can’t argue. That’s why he stays in the country. Just under six-feet tall, he’s a broad-shouldered guy, with a clean-cut beard, Native American roots and southern accent. Like Qubein, the 29-year-old weathered a difficult journey to get here. He fell into homelessness, declared himself emancipated and survived as an unaccompanied youth. After working his way through high school and community college, Curtis has his business degree from UNCG, so Jake’s is familiar turf. He lights a cigarette and looks into the background. As Market brings in billions of dollars year, he insists there’s still so much money to be made working in High Point’s furniture scene. He hears the critics who say millennials don’t work the same way older generations did. But no matter how much you grind, the rewards seem harder to find. Right now, he’s on hiatus from showrooms, working for a moving company. “There’s people who don’t want to work and there’s people who will bust their ass off and barely get paid,” he tells me.

Tonight is a celebration of sorts, so we were really hoping a booth would open up for dinner soon. About four years ago, Will and Curtis met while working in the Asian Loft showroom during Market. They became friends and are committed to ideas for more off-peak business, including joining an association that plans events to lure in designers. Will’s hard work as a bartender at the String & Splinter led Miss Nicki to promote him to administrative assistant – a better deal for now. Showroom job hours are long and the pay tends to be low. Unlike Qubein, Will and Curtis don’t have connections to get to the top – yet. To make it in furniture, you have to be in sales, or part-ownership or be a good enough designer to have your face on a billboard during market, they say. “Instead of passing the torch on to someone younger and teaching and spending a lot of money to get you there to move on and take over…” Will says. “No upward mobility for people our age?” I ask. “Very tough,” he replies. “Very tough.” Curtis dives into his plate of quesadillas. I burn my tongue on a piping hot fried pickle. Will’s chicken fingers are doused in BBQ sauce, just the way he wanted them. “Cheers!” we yell as we raise our glasses. The food and pool table were worth the wait. Jake’s was the kind of place worth driving, even if it was a bit far.

I lost track of how many other places we went to during the course of the night, but tried to keep count by Uber ride. The first one took us back to Jake’s after we put my car away for safekeeping. The driver could have been a former mayor – a soft-spoken black man who lived in the area for 47 years. He had no idea the Rockers were coming to High Point, but figured we were spenders tonight. “We used to drink in the Walmart parking lot, which was a lot cheaper,” he says. The second brought us downtown to Boxcar Bar + Arcade, a monstrous hotspot with 100 games, 24 beers on tap, cups of free popcorn and piping hot pizza on the patio. It opened last April, and somehow, Greensboro had one before Durham. The driver was around our age and got us there quickly. Another friend, Cody, who joined us midway through the night, grabbed his number. I didn’t understand why until around 2 a.m., when we needed that third-and-final ride, and hit a bit of a bind.

Thankfully the guys filled up on two pizzas before we headed home. Surge pricing was through the roof, at around 25 bucks just to get back to my hotel. Randleman was another 15 miles away. Gate City Boulevard was a ghost town at this hour – gas stations and auto body shops, mixed in with UNCG apartments and hints of gentrification, like a new greenway. We passed one building and saw a light on in a first-floor unit, as well as a head of hair sticking out from under a pillow. “That’s not a good idea,” Will says. We all knew those open blinds were vulnerable. Curtis was dying to order the Uber, but if we got a little closer to Jake’s, the bill would drop down to 15 bucks. We kept walking, and walking, and walking. Cody sang the Beach Boys’ “I Get Around!” to pass the ride wait time. My Apple Watch, which rarely gets any activity after midnight, was already at 5,000 steps. I slipped Will a $20 bill for the ride and we all hung out inside the hotel for a few minutes, until the next Uber came. It ended up being the same driver who just dropped us off. Will was headed back to his dad’s house in Jamestown. Curtis and Cody were splitting the ride to Randleman. This was easiest, for now. I kept thinking about something Curtis said earlier about furniture, wondering if it applied to nightlife too. You really can’t believe anything in High Point until you see it.